|

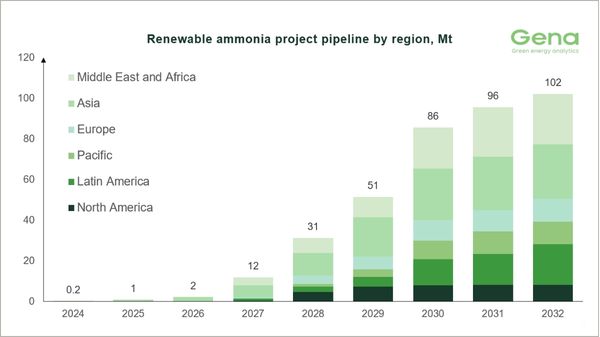

Clean ammonia project pipeline shrinks as offtake agreements remain scarce

Renewable ammonia pipeline falls 0.9 Mt while only 3% of projects secure binding supply deals. |

|

|

|

||

|

Thoen Bio Energy joins Global Ethanol Association

Shipping group with Brazilian ethanol ties becomes member as association plans export-focused project group. |

|

|

|

||

|

Norway enforces zero-emission rules for cruise ships in World Heritage fjords

Passenger vessels under 10,000 GT must use zero-emission fuels in Geirangerfjord and Nærøyfjord from January 2026. |

|

|

|

||

|

Longitude unveils compact PSV design targeting cost efficiency

Design consultancy launches D-Flex vessel as a cost-efficient alternative to larger platform supply vessels. |

|

|

|

||

|

IBIA seeks advisor for technical, regulatory and training role

Remote position will support the association’s IMO and EU engagement and member training activities. |

|

|

|

||

|

Barents NaturGass begins LNG bunkering operations for Havila Kystruten in Hammerfest

Norwegian supplier completes first truck-to-ship operation using newly approved two-truck simultaneous bunkering design. |

|

|

|

||

|

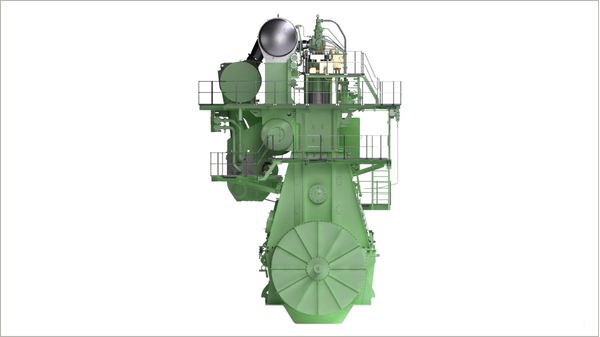

Everllence receives 2,000th dual-fuel engine order from Cosco

Chinese shipping line orders 12 methane-fuelled engines for new 18,000-teu container vessels. |

|

|

|

||

|

NYK signs long-term charter deals with Cheniere for new LNG carriers

Japanese shipping company partners with Ocean Yield for vessels to be delivered from 2028. |

|

|

|

||

|

Sallaum Lines takes delivery of LNG-powered container vessel MV Ocean Legacy

Shipping company receives new dual-fuel vessel from Chinese shipyard as part of fleet modernisation programme. |

|

|

|

||

|

Rotterdam bio-LNG bunkering surges sixfold as alternative marine fuels gain traction

Port handled 17,644 cbm of bio-LNG in 2025, while biomethanol volumes tripled year-on-year. |

|

|

|

||